address

Arklių g. 5, Vilnius

number of theatre staff

62

auditoriums

2

theatre building opened

1975

texts

Kostas Biliūnas

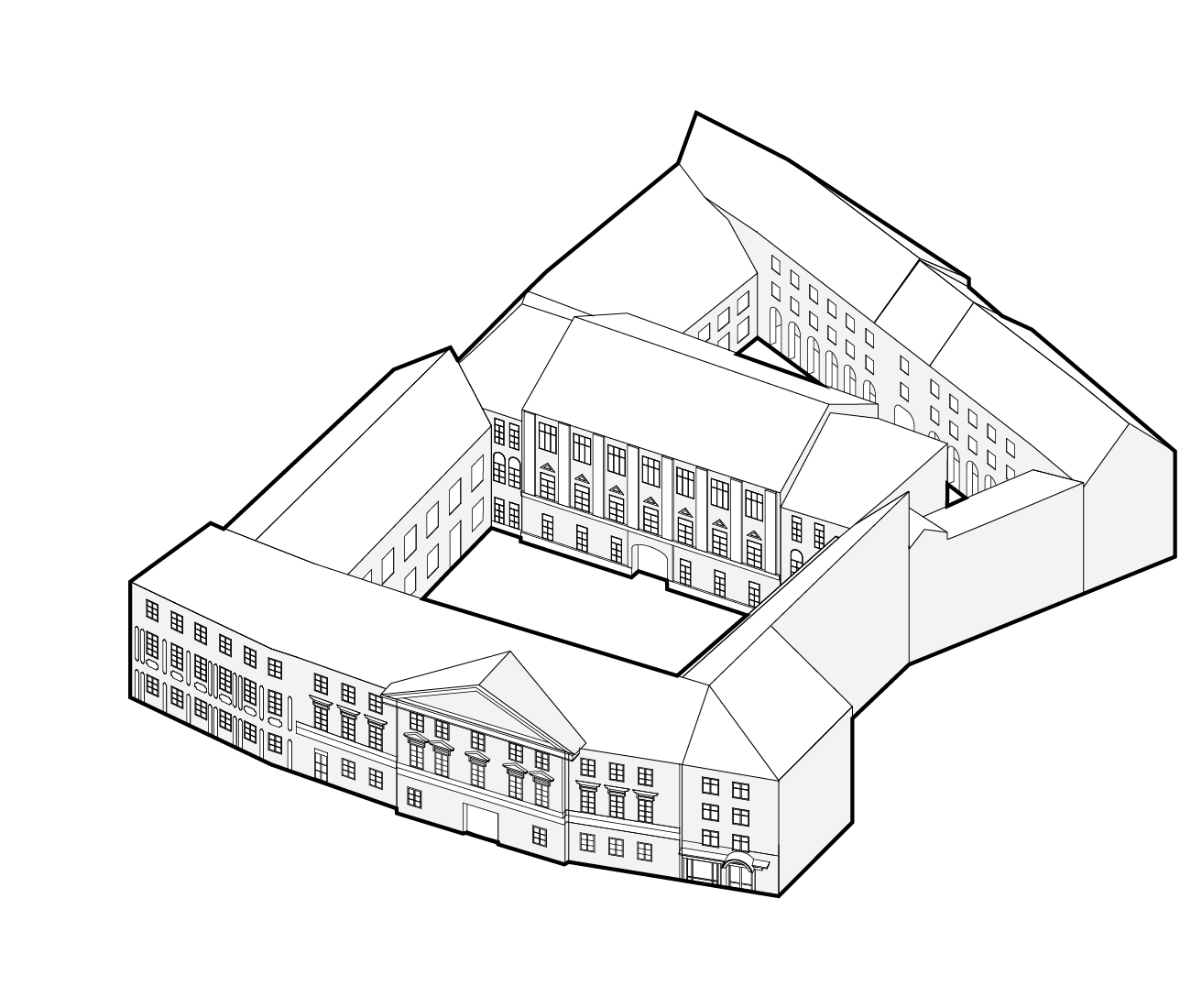

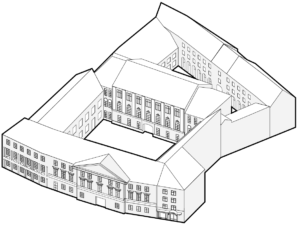

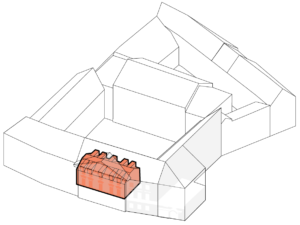

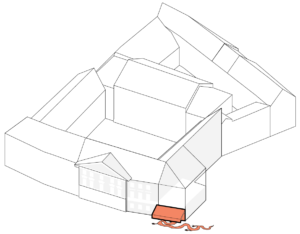

A palace that for two centuries housed the Princely Ogiński Family eventually became home to the Vilnius Theatre “Lėlė”. The palace was originally conceived of in the 18th Century as one huge, unified complex that not only connected Arklių and Rūdninkų Streets but also spilled over into the Old Town. Today, the largest former residence of nobility in the capital city of Vilnius is divided around two large, enclosed courtyards. In 1771, under the auspices of Grand Marshall Ogiński, older houses in the area were reconstructed into a palace around a spacious 2,600 square-meter courtyard. This expansion went even further. After King Augustas III granted permission to demolish houses in front of the entrance to the palace, Ogiński constructed Perspective* Street (currently Etmonų g.) that revealed an unobstructed view of the palace. To enhance this view’s effect, the new street was framed with two symmetrical auxiliary buildings. Today, a small square creates synergy between the palace (which now houses the Vilnius Theatre “Lėlė” as well as the Youth Theatre) and its outer buildings, which currently contain nightlife bars popular with the young people of Vilnius.

The entire Baroque architectural ensemble looks almost as if it has been somewhat crookedly strung along a line following the curves of the Old Town. At the centre of this curved axis lies the most important part of the palace – the Great Hall. As in other Baroque residences (e.g. those of the Pac or Chodkiewicz families), the largest room for formal receptions was situated directly above the gateway to the most ornately beautiful floor – the bel étage. This Great Hall for feasts, celebrations and dances was special not only because of its twenty windows that symmetrically lit its ceiling and parquet wooden floor, but also because of the views through its windows: on one side there was Perspective Street and on the other – the Baroque façade of the palace itself across a spacious courtyard. Today, this hall houses the Vilnius Theatre “Lėlė”.

The last person to use the palace for his residence was the famous diplomat and composer Michał Kleofas Ogiński who was a member of the Kosciuszko Uprising. A romantic tale is often depicted at the Theatre “Lėlė” that in the 19th century Prince Ogiński sought to create a theatre at the palace. This legend is indeed based upon fact. Having recently returned from Paris where he saw an opera by Zingarelli at the Théâtre des Tuileries, Ogiński immersed himself in Vilnius’ cultural life. Although operas were already being staged in Vilnius, they were very poorly funded. Therefore, Vilnius’s cultural elite, including the esteemed Doctor Józef Frank and Ogiński himself, conceived the creation of a National Theatre. “The aim of the new National Theatre of Lithuania is to bring foreign masterpieces onto our nation’s soil, to disaccustom people from those pleasures that are harmful to traditions and their health [and others]. Count Ogiński deeds over a part of his palace in Vilnius to the Theatre” (Frank, p. 303). However, this plan never proceeded.

* We suggest this translation of the Polish ulica Prospektowa, because in the late 18th–early 19th century, prospekt meant a view or perspective, only later referring to a wide central street.

The Ogiński Palace in the late 18th century, reconstruction, 2025, design by E. Vasiliauskaitė

The palace was owned by seven entire generations of the Ogiński family. However, in the 19th century, when the Rietavas estate in Lithuania became the extensive family’s main place of residence, their palace in Vilnius was leased out and, over time, became more income-generating real estate rather than a residence. One of the palace’s tenants was the Vilnius Club of Nobles. A photograph in the popular fin-de-siècle magazine Illustrated Life depicts one of the club’s banquets in the Ogiński Grand Hall. The club’s main activity was described as, “pleasant entertainment for themselves through the organization of public, respectable and inexpensive amusements”. (Griškaitė, p. 44).

The photograph seems to show the back wall where a stage would later be built. In the centre is perhaps a portrait of the Russian Czar and on the left stands a tiled fireplace. On the right there is a door into a space that later became a stage. Other rooms in the palace housed offices and apartments. Numerous Jewish families lived there, and the community included both a Jewish high school and a synagogue. When Polish forces expelled Lithuanian teenagers from the Vytautas the Great High School in 1921, the Jewish school in the Ogiński Palace took in the displaced Lithuanian students.

During World War II, the Nazis established the Large Ghetto around Rūdninkų Street. This marked just the first stage of their systematic genocide. The Ogiński Palace found itself inside the Jewish ghetto and became one of its most important centres. First, a Judenrat — a Jewish governing body subordinate to the Nazis — was established. The Vilnius Ghetto Theatre, a unique manifestation in Europe, emerged from the Large Ghetto. In April 1942, the theatre moved to the old Ogiński Hall, opposite the Judenrat windows, and operated there until the liquidation of the ghetto in 1943. There was outrage and leaflets were distributed with the headline, “Can you produce theatre in a graveyard?” (Kruk, p. 175). Nevertheless, the theatre provided entertainment, and it attracted much interest.

Decades later, actor and director Israel Segal, a survivor of the Holocaust, recalled working in the Vilnius Ghetto Theatre, “We performed as well as we could in light of our circumstances and according to which actors were still alive” (Sobolis, p. 65). It is impossible to grasp what it meant to act in that theatre – we can only rely on the words of survivors. The theatre was the cultural heart of the ghetto: productions of practically all genres were staged there – including classical music concerts, art exhibitions, puppet shows, and musical comedies. The theatre’s hall was reached through the Ogiński Palace gateway on Rūdninkų Street. It was also through that gateway that the last actors of the Vilnius Ghetto Theatre departed.

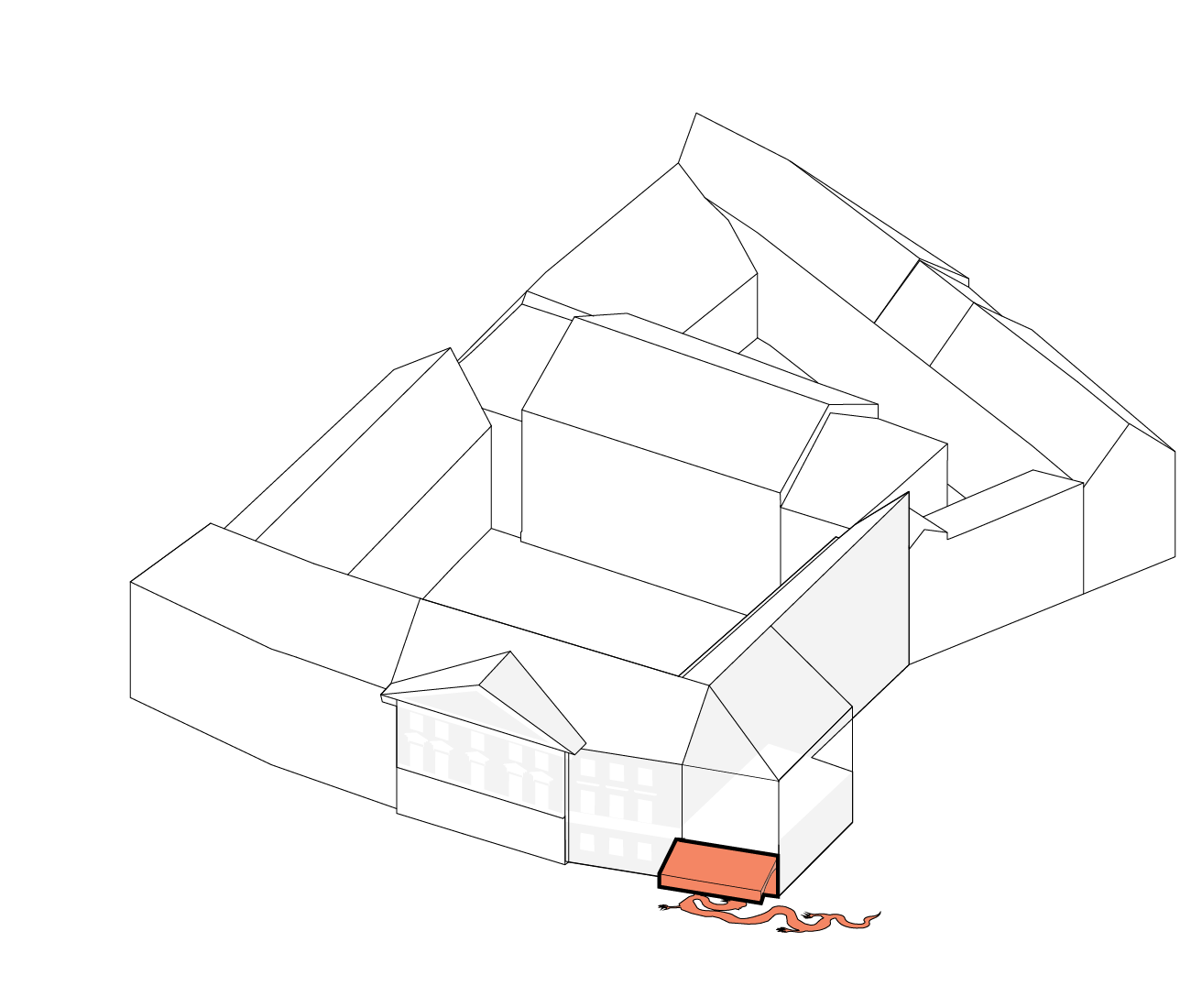

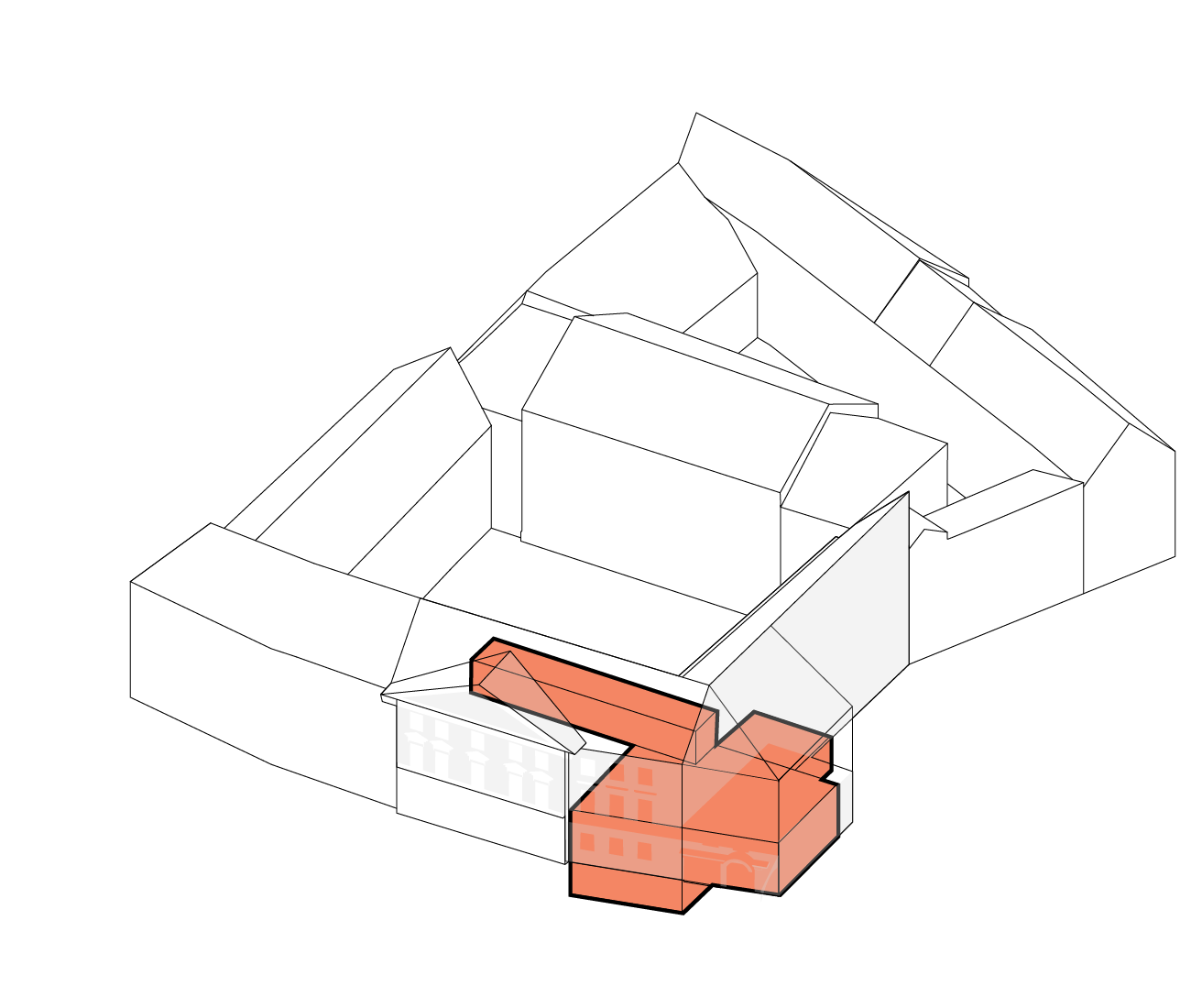

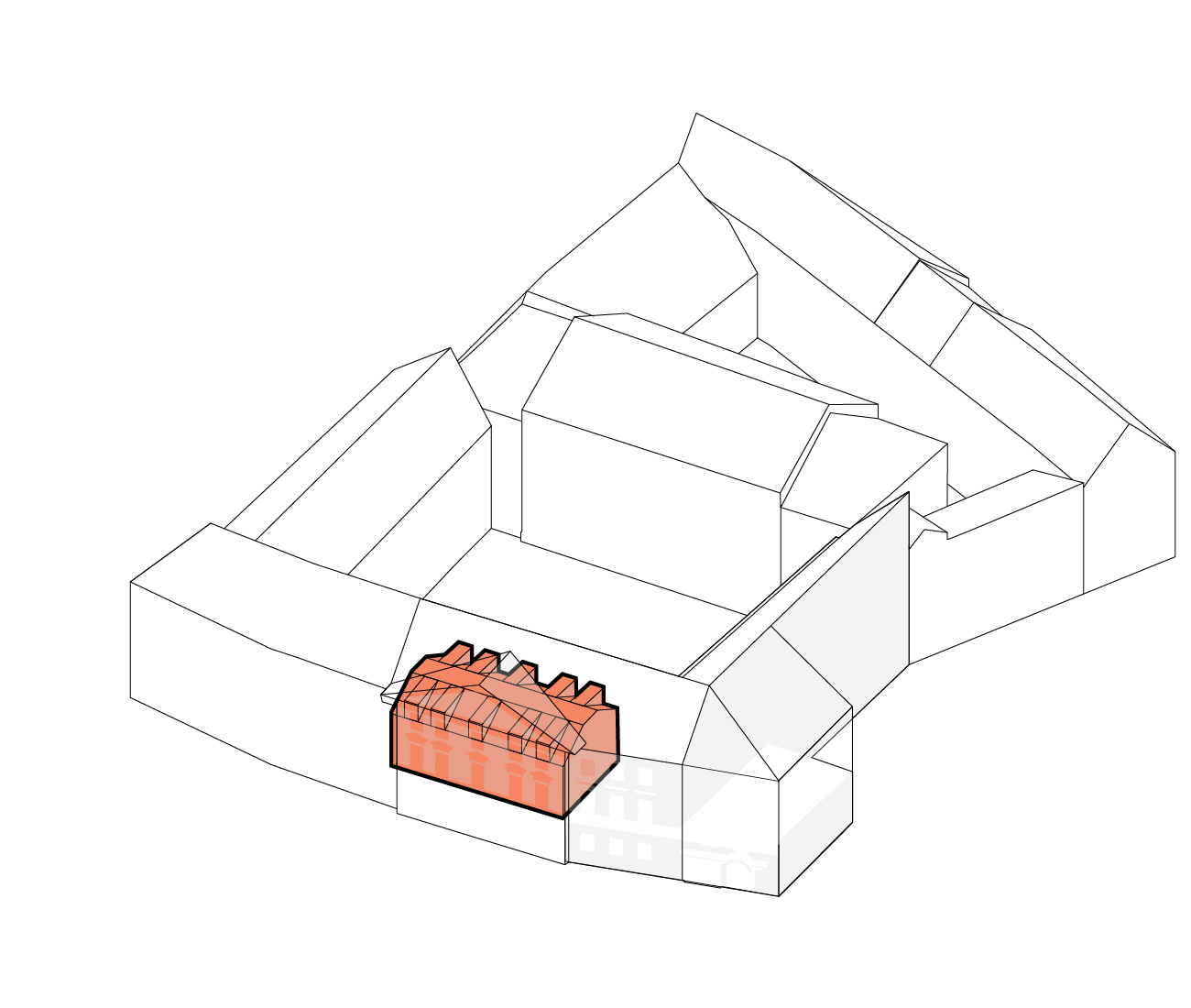

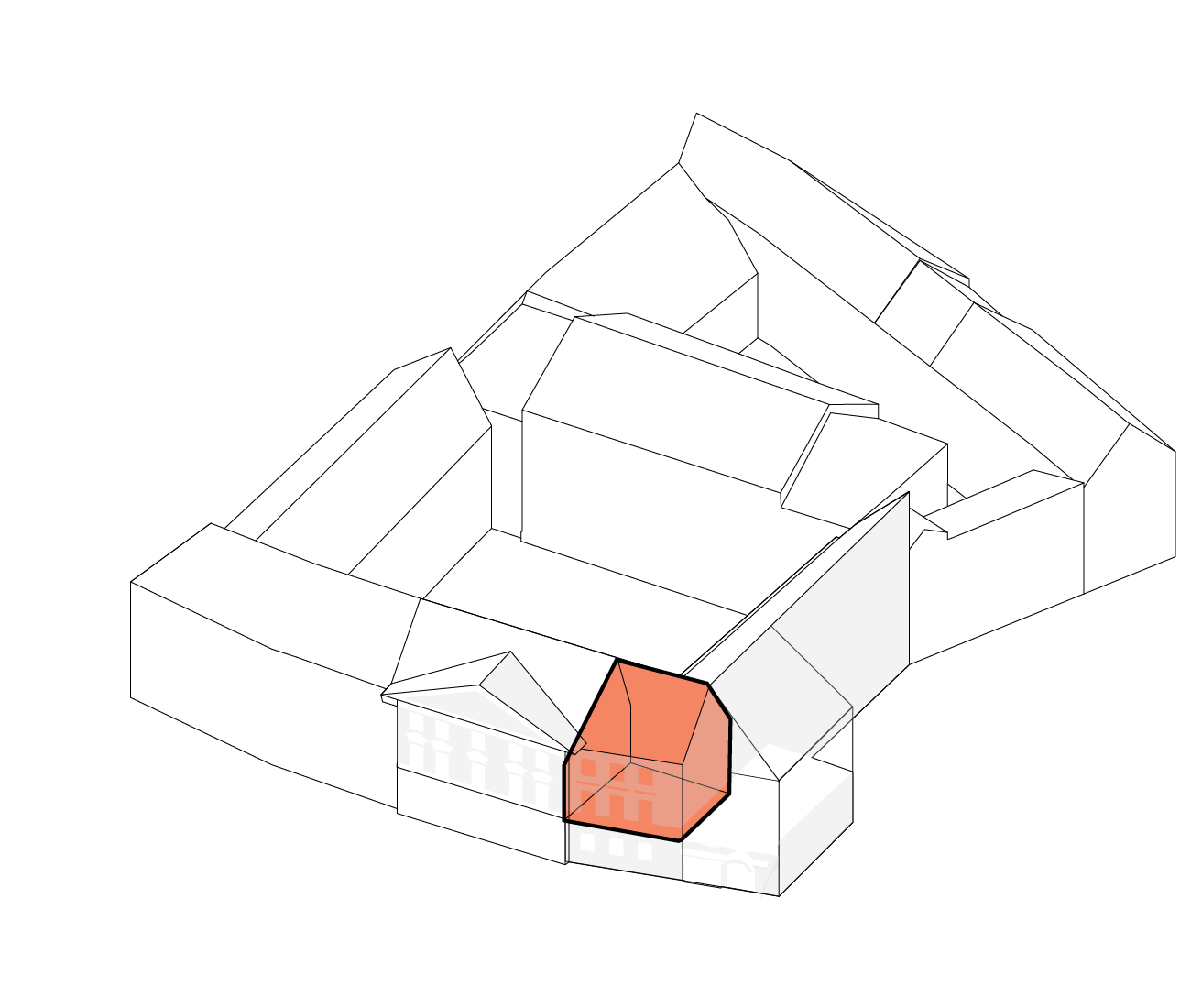

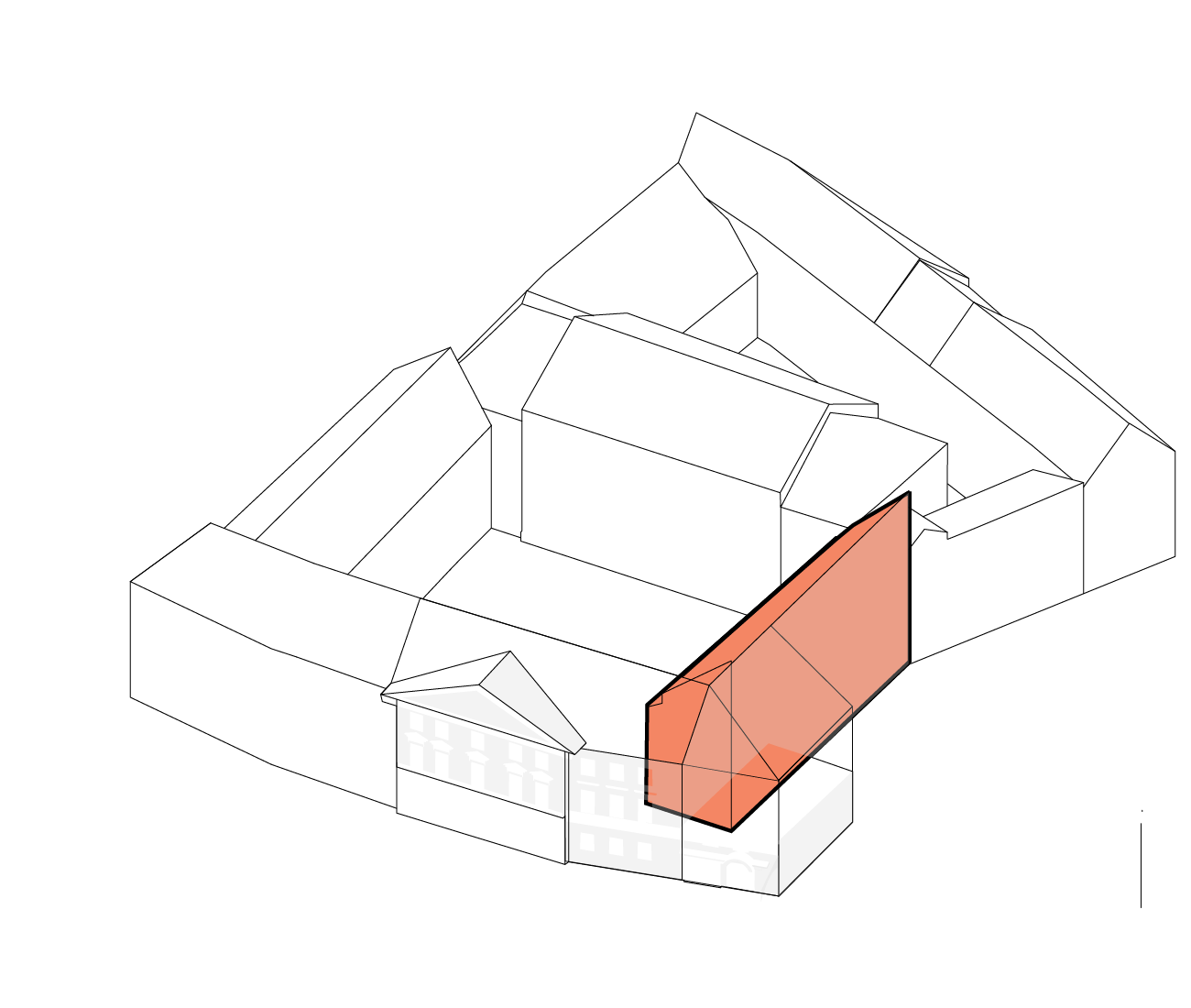

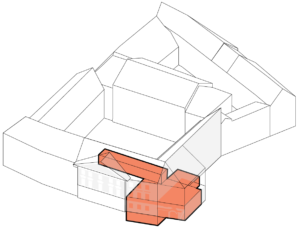

The Ogiński Palace in the mid-20th century, 2025, design by E. Vasiliauskaitė

The Ogiński Palace was reconstructed into a theatre between 1972 and 1975. The architects in charge were Vitalija Stepulienė, Antanas Kunigėlis and Birutė Čibiraitė-Biekšienė. After World War II, the Grand Hall had been used by the Ministry of the Protection of Public Order or, as it was more simply called – the Militsiya Club. The first task, as architect V. Stepulienė recounts, was the “simple” adaptation of the Militsiya Club for the Youth Theatre. Only when the design phase had begun did it become clear that the central part of the palace was unsuitable for a large theatre – a fly tower rising above roof level would have brutally changed the Ogiński Palace’s appearance. Even by Soviet standards, this didn’t seem like it would be a good decision. An alternative solution was found: to move the drama theatre to a more remote part of the palace and to adapt the Great Hall for a puppet theatre which needed less space.

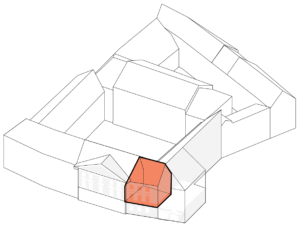

“Look at the theatre’s entrance. No one would think that the narrow door leads into a theatre and that someone is waiting here for guests,” theatre critic Audronė Girdzijauskaitė wrote at the end of the Soviet occupation period (p. 16). For decades, the entrance was indeed easy to miss — it was the only part of the project left unbuilt because Moscow never granted approval. Today, walking from Town Hall along Arklių Street towards the Theatre, one is guided by Aušra Bagočiūnaitė-Paukštienė’s mural On the Way (2016). According to the unrealized project, a dragon mosaic curling along the pavement would have led you to the theatre in the shape of an “sss”.

Modernist ceramicist Ignas Egidijus Talmantas, working with the architects, envisioned a curved canopy spanning the entire street — echoing the arches of Vilnius’s old quarters — to shield visitors from rain and snow. Evoking the era when the Ogiński nobles lived there, the auxiliary building across the street was to be repurposed for visitors, housing a ticket office and utility rooms. The dragon embedded in the pavement tiles was to be complemented by a clock with moving figures, also designed by Talmantas, set into a niche in the building’s façade. A design had also been prepared for glazed entrance doors with brass details, but, alas, everything was destined to remain on paper.

After World War II, the entrance to the Militsiya Club was through the carriage gateway, although that was obliterated when the Youth Theatre lobby was built in the 1980s. A new entrance to the Theatre “Lėlė” was created through a block of flats nearby. It was only in 2000 that architect Saulius Leinartas gave the entrance a form reminiscent of arches, filled with puppets by Bagočiūnaitė-Paukštienė. The Theatre “Lėlė” had finally gained a visually commanding entrance.

Designing the theatre’s interior faced Soviet occupation era challenges: some decisions were “handed down from above” and a number of ideas were not approved. This occurred with entryways to the Theatre “Lėlė”. The interior of the small foyer wasn’t shaped by a deliberate architectural choice, but by leftover marble flooring from the recently completed Opera Theatre. The marble came from large Soviet marble quarries located at Koelga, a town beyond the Ural Mountains near Kazakhstan. The light and dark grey hued stone with light veining is one of the few authentic interior elements in the Theatre “Lėlė” to have survived subsequent renovations. Working under restrictive circumstances allowed the architects to find a distinctive combination. As a counterpoint to the grey marble, the walls and ceiling of the ground floor were painted a rich “English” red. And thus, utilizing minimal means, an impressive result was achieved.

The brightly coloured scheme created a main theme for the interior. The original palette has partly survived in the Great Hall, combining a rich red ground floor foyer with a dark burgundy coloured hall and a soft lilac second-floor foyer. Sketches show these colours complemented by a mustard yellow vestibule. This striking and dynamic combination, reminiscent of Chinese art, was echoed in the unbuilt dragon mosaic planned for Arklių Street. We can only guess that the dragon itself was meant to be red.

The balustrades of the metal staircase designed by architect Čibiraitė-Biekšienė are another authentic element. Their op-art-like motifs are repeated in all other staircases of the Theatre “Lėlė”, and the metal pattern seems to ripple as you climb. An illusion of space was also created by four stained-glass panels designed by Algirdas Dovydėnas. These light and bright panels are among his most important works. In similar segments, figures reminiscent of coloured brush strokes float in squares of light. Today, only one panel, relocated to the staircase, can be seen; the others have been disassembled for preservation.

In the foyer, only the walls and arches recall the Baroque palace. An even older part lies beneath it – the cellars. During the era of Soviet occupation, there were plans to relocate the Small Hall in them and this was finally done in 1992. Nearby in the old cellar is the Theatre “Lėlė” museum.

From the outside, it’s hard to tell which part of the palace the Theatre “Lėlė” occupies. Although one enters through an annex, the Great Hall of the theatre is at the very centre of the historic palace, directly above the entrance to the Youth Theatre. It’s not known when the hall acquired its most recognizable feature – the wooden ceiling imitating an attic. Although gilded with real gold rocailles, this is not an 18th-century interior. The orderly arrangement of the ornamentation suggests that the ceiling dates from the Neo-Rococo period of 1890–1905. The coffered ceiling may have been installed for a very practical reason: to keep the hall as warm as possible. By then, a gallery had been added on the courtyard side, yet there were still 15 windows, so winter evening fests were hardly warm. Three stoves served to heat the room. Another theory is that the ceiling was installed to improve acoustics.

After World War II, all the rooms in the palace were close to collapse until historical research was carried out in 1964 and it was repurposed as a cultural centre (architects Vytautas Dvariškis and Romanas Jaloveckas). The Great Hall was singled out as the only interior room to be preserved. However, only the ceiling was preserved; the tiled fireplaces and the old entrance to the Great Hall (which would eventually lead to the foyer of the Youth Theatre) were torn down. During this proletarian Soviet occupation era, the Baroque rooms were deemed to be without value.

Looking up at the ceiling, one’s attention is drawn to the chandelier. Although it seems to have organically grown out of the ornate ceiling, the fixture only made its appearance here during the reconstruction of the Theatre “Lėlė”. Architect Kunigėlis had found it in the attic of an historic building. The chandelier was made of papier-mâché and was then restored, gilded and adapted for electric light. The ceiling with moldings was also carefully restored and, after cleaning off the bronze paint, the surviving ornamentation was gilded once again. Wide air ducts needed for large audiences were ingeniously hidden in the historic ceiling’s structure.

Noteworthy are the chairs created by the reconstruction’s architects. Simple chairs were completely transformed through design. Folded up, they raised a young spectator’s eye level and became suitable for a small child. Special footrests were also designed. Although these design solutions weren’t totally successful, when the chairs were replaced with new ones, the same 1970s idea was retained.

After World War II, all the rooms in the palace were close to collapse until historical research was carried out in 1964 and it was repurposed as a cultural centre (architects Vytautas Dvariškis and Romanas Jaloveckas). The Great Hall was singled out as the only interior room to be preserved. However, only the ceiling was preserved; the tiled fireplaces and the old entrance to the Great Hall (which would eventually lead to the foyer of the Youth Theatre) were torn down. During this proletarian Soviet occupation era, the Baroque rooms were deemed to be without value.

Looking up at the ceiling, one’s attention is drawn to the chandelier. Although it seems to have organically grown out of the ornate ceiling, the fixture only made its appearance here during the reconstruction of the Theatre “Lėlė”. Architect Kunigėlis had found it in the attic of an historic building. The chandelier was made of papier-mâché and was then restored, gilded and adapted for electric light. The ceiling with moldings was also carefully restored and, after cleaning off the bronze paint, the surviving ornamentation was gilded once again. Wide air ducts needed for large audiences were ingeniously hidden in the historic ceiling’s structure.

Noteworthy are the chairs created by the reconstruction’s architects. Simple chairs were completely transformed through design. Folded up, they raised a young spectator’s eye level and became suitable for a small child. Special footrests were also designed. Although these design solutions weren’t totally successful, when the chairs were replaced with new ones, the same 1970s idea was retained.

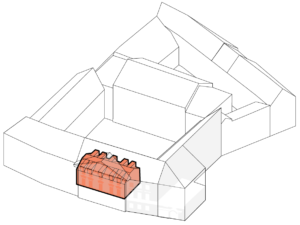

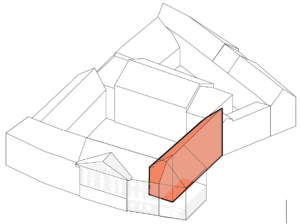

The fly tower that soars above the Theatre “Lėlė” roof cannot be seen from the outside. And yet, this indispensable part of the theatre occupies as much space as the historic third-floor rooms and attic under the tiled roof once did. After demolishing that part of the palace, a reinforced-concrete stage house had been created, not in a usual rectangular form but with a pitched roof.

This stage, located next to the old Baroque Grand Hall, was most likely created in the 1930s, when Polish, Jewish and Lithuanian acting troupes performed there at various times and the space was known as the Small City Hall. It was decided to house the Militsiya Club there as the space already had a hall and a stage. Nevertheless, this was insufficient for a professional theatre. To make scenery changes during a performance and to smoothly organize productions, the stage space had to be expanded upward so that decorations, lighting and other machinery could be lifted into the “pocket” of the reinforced-concrete shell. The Theatre “Lėlė” stage equipment had been designed by long-time theatre artist and scenographer Vitalijus Mazūras. At first, the stage’s technical possibilities were supplemented by a shallow lifting platform and a stationary curved metal screen at the rear. These were later removed.

“Lėlė” was designed at the time when the Central Puppet Theatre opened in Moscow (1971, architects Yuri Sheverdayev, Aleksei Melekhov, Valentin Utkin) – the largest theatre building of its type. The architect Stepulienė visited it specially at that time. It became clear that it was hardly possible to apply the designs she saw in Russia to Lithuania because the Theatre “Lėlė” had to continually address problems of limited space. To compensate for the smaller volume of the stage box, the proscenium arch that was reminiscent of the Vilnius Club of Nobles was lowered. Its semi-oval silhouette, that was evocative of the Great City Hall (currently Philharmonic Hall), was straightened out. Its decorative symbol of a lyre with branches at the top of the arch also disappeared.

After simplifying the stage arch, two compositions resembling “ears” were designed on either side, allowing for hidden spotlights and speakers. During the reconstruction carried out since 2017 (architect Nijolė Ščiogolevienė), with these elements removed, the Neo-Rococo ceiling was revealed; however, the architectural composition became poorer. Even less of the 1970s interior remained after the removal of the “Whirlpools” stage curtain and door drapes. They were artworks done by one of the most original textile artists of the Soviet occupation era, Medardas Šimelis. During conditions of Soviet scarcity and only having access to white velvet, he dyed patchwork pieces of it in many colours in his studio. During the theatre’s last renovation, Šimelis’ well-worn textiles were removed. The unique stage curtain, unparalleled in Lithuania, is now treasured in the Lithuanian National Museum of Art.

Although it may seem that the Theatre “Lėlė” premises are now scattered throughout the original Ogiński Palace, in fact they occupy an L-shaped segment – a quarter of the former rectangular palace with a spacious courtyard at its centre. This almost completely corresponds to the old Pawłowicz house, which Marcjan Michał Ogiński bought in 1729 and from which he began to form his Baroque residence. Earlier, in the 17th century, this part was a separate house occupied by the Dzewlewski and later the Pawłowicz families. Thus, the long part of the “L” stretching into the block is as old as the palace’s Great Hall itself. This section can only be viewed from the inner courtyard and contains all the theatre’s “invisible” functions.

In the 19th century, when the Ogiński family moved from Vilnius to their residence in Rietavas and their palace in Vilnius was leased out, the Pawłowicz section of it housed the Nobles’ Charity Office and the District Court. The floors of today’s Theatre “Lėlė” were once regularly trodden by members of these institutions and the Club of Nobles—aristocrats, officers, scholars, and even well-to-do townspeople. There were probably offices on the ground floor which visitors entered directly from the courtyard. Until reconstruction, the longer wing was divided into small rooms that each had a window. Today, a very similar layout remains on the first floor. The entire current wing of the theatre was exclusively within the purview of the nobility in the 19th century – both their charitable organization and leisure club were located here.

Soviet-period reconstruction of this historic building introduced changes incompatible with today’s heritage conservation norms, but, overall, this was not the worst possible case scenario for Vilnius’ Old Town. Original arched vaults are still visible in various places on the ground floor and underneath them there are the administrative offices of the Theatre “Lėlė”. A café is open during performances in a part of the long wing.

There are workshops for metal, wood and plastics, and rooms for making and storing puppets and sets on the first floor. The second floor was fitted out when adapting the palace for the Militsiya Club (around 1965). Standard Soviet occupation era windows clearly distinguish this floor from the old palace. In 2013, a fourth attic floor was added, featuring a small rehearsal room. Along its length runs a firewall pierced with arches marking the boundary of the Ogiński property. It last protected the palace from fire in 1947, when the adjoining so-called Conservatory building burned down. Now that plot is empty and is fenced off from Arklių Street.

Founded in 1958, the Vilnius Theatre “Lėlė” operated for almost two decades without a hall, and fifty years ago welcomed audiences to its new home in the historic Ogiński Palace. Over half a century, “Lėlė” has become an inseparable part of Vilnius Old Town.

Theatre’s courtyard wing, 2025. Photo by M. Plepys

Čaplinskas, A. R. Road of Rulers, Book 1: Rūdninkų Street. Vilnius: Charibdė, 2001.

Driežis, R. “History of a Building”. Vilnius Theatre Lėlė, https://www.teatraslele.lt/pastato-istorija/.

Dvariškis, V., Jeloveckas, R. Lithuanian SSR Club of the Ministry for the Protection of Public Order, 5 Arklių Street. “Explanatory Memorandum.” 1964, Heritage Protection Library, f. 5, ap. 1, b. 69.

Frank, J. Memories of Vilnius. Vilnius: Mintis, 2013.

Girdzijauskaitė, A. “Seven Days”, Literature and Art, February 6, 1988.

Griškaitė, R. “Dancing Vilnius”, from: Z. Medišauskienė (ed.), Stories about Vilnius and Its Residents, Vol. 3 Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2020.

Interview with Vitalija Stepulienė and Birutė Čibiraitė-Biekšienė by K. Biliūnas, 2025.

Jučienė, I. “Childrens’ Puppet Theatre, Vilnius, 5 Arklių Street (the former Ogiński Palace).” Historical Research,1971. VRVA, f. 1019, fld. 11, b. 5020.

Kruk, H. Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania: Chronicles of the Vilnius Ghetto and Camps, 1939–1944. Vilnius: Center for the Study of Genocide and Resistance by Lithuanians, 2004.

Mačiulis, A. Art in Architecture. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, 2003.

Markejevaitė, L., ed. Frozen Music: Palace of the National Opera and Ballet Theatre in Vilnius. Vilnius: Artseria, 2021.

Sobolis, J. “Interview with Israel Segal.” Shores, no. 3 (1997).

Vitkauskienė, B. R. and K. Glinska. Rediscovered Vilnius: City Model’s Cartographic and Sociotopographic Sources. Vilnius: Lithuanian National Museum, 2023.

Zaluskis, A. Michał Kleofas Ogiński: Life, Work, and Legacy. Vilnius: Center for Regional Cultural Initiatives, 2015.