address

J. Basanavičiaus g. 13

number of theatre staff

104

auditoriums

2

theatre building opened

1913

texts

Kostas Biliūnas

Since the middle of the 19th century, performances in Russian dominated the main centre of Vilnius theatre life – the town hall. When Polish performances were also allowed in the early twentieth century, they were originally shown in unheated wooden summer theatre and circus buildings. The necessity to build a separate brick theatre building for the Polish community was quite big, but the greatest challenge was raising funds for this private initiative. 1911 on the initiative of the Polish elite – Klementyna Tyszkiewicz, Hipolit Korwin-Milewski, Feliks Zawadzki and others – a partnership was established, which then accumulated the initial capital required for the construction of the theatre. The choice of the location of the land lot was discussed in the partnership – excluding the more expensive options in St. George (now Gediminas) Avenue, a cheaper and more spacious plot on Wielka Pohulanka Street (now J. Basanavičiaus) was chosen.

The original project of the Polish Theatre by an unknown author in 1911, prepared in the absence of a specific land lot, was formed in the established language of historicist architecture. As usual, the historical styles are ‘quoted’ here according to the necessary impression: Renaissance and Neoclassicism – for the solemn façade, Baroque – for the ornate and luxurious interior of the hall. Such a standardized construction of architecture, based on quotes from past centuries, was also directly related to the ritual of visiting the middle class theatre. The architecture of the theatre keeps the most important stages of this ritual. However, the building on Wielka Pohulanka Street, erected just before the First World War had little resemblance to the theatre of Historicism, which is why its architecture, although using the same traditional elements, speaks already a new, twentieth-century language.

Opened in 1913, the theatre was built according to the design of the winning Vilnius architects Wacław Michniewicz and Aleksander Parczewski (architecture office “Architekt”). Although the authors withdrew from the building as a result of a conflict and the construction work was supervised by another architect from Warsaw, the original design was followed and only later was the interior redevelopment aimed at improving the ergonomics of the theatre itself.

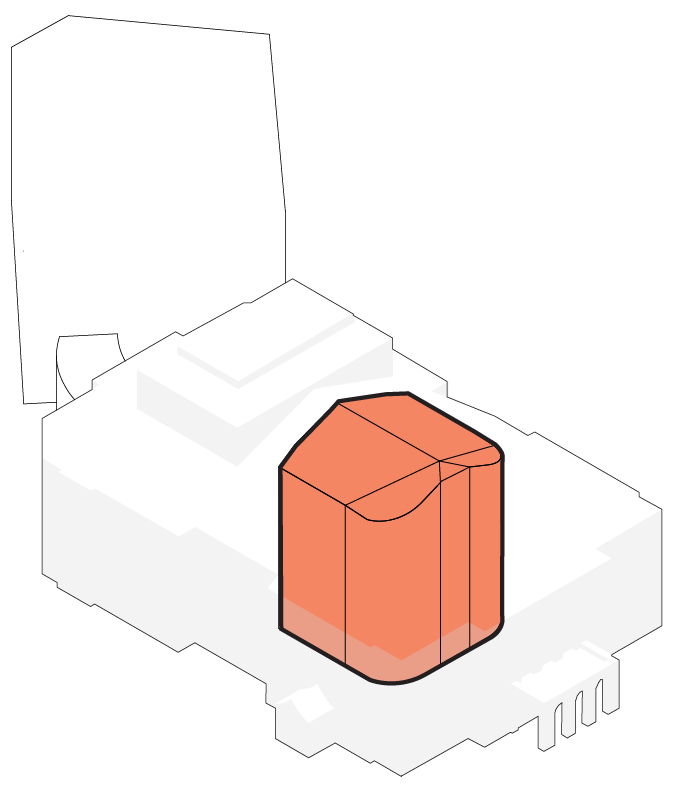

The exterior of the building has not been altered during subsequent reconstructions, and it largely reflects the novelty that Art Nouveau, which replaced Historicism, brought to architectural thinking. This novelty can be best seen in comparison to the architecture of a traditional historicist theatre (e.g., the original 1911 project). Traditionally, the main façade of the theatre was strictly symmetrical, based on an ordering system, and occupied a central place in the structure of the entire building. However, the architecture of the Polish theatre no longer follows this established model of Historicism. At the Michniewicz and Parczewski theatre, all these rules were abandoned – although the main façade is symmetrical, the building itself has been turned so that it is mostly viewed from the side or angle. In this way, different façades change and overlap, and the façade gives way to the emerging concept of the building as a single volume – later it will be broadly developed in modernist architecture. With the abandonment of the previously mandatory order system, the main façade is made up of fragments of Romanesque, Renaissance, Baroque architecture and is no longer dominant. Passing by, the twisted position of the theatre allows you to watch the ever-changing perspective, and the hill provides an opportunity to draw attention to the ‘fifth façade’ – a complex broken roof with the stage growing out of it.

Ascending or descending the former Wielka Pohulanka Street, the entire volume of the theatre building emerges like a mountain or a huge sleeping animal. Although composed quoting previous styles, but with its integrity, the organic connection between the different façades and the roof, this building is already beginning to draw a new direction towards the modernist architecture of later decades.

Although the architecture of the Polish theatre reveals a new way of thinking signalling Art Nouveau, its elements, although not so obvious, have been taken over from 19th century theatre. This was a concept that predominated for a long time, but is already vanishing at the time of the emergence of the Polish theatre, consisting of a certain sequence of architectural spaces that forms the ritual of visiting a theatre. In the 19th century, the importance of this ritual was the same (if not more important) than the process of watching the play itself, and the elements that make up this sequence were recognizable in any theatre building.

The ritual begins on arrival. In the 18th century, an element of a portico attached to the façade (a covered gallery) was formed, through which carriages took and left visitors directly to the theatre. Such a gallery, although small, is also on the main façade of the Polish Theatre. In order for the carriages to move well, a ring-shaped access was formed in place of the current square, which consisted of two sloping ramps. They were taken up on arrival and descended on departure. Until the 1930s, the most popular means of transport in Vilnius were single-horse carriages. During the reconstruction of the theatre in 1947, the eastern ramp leading to the gallery was dismantled as it became obsolete, and stairs were installed in its place, which are more reminiscent of the natural relief of the plot.

In the first hall room, ever since the construction of the theatre, a portal and a double entrance door were installed to retain heat. On the left side of the hall there was the box office.

An integral part of the theatrical ritual is the great staircase, which used to be installed in the centre of an historicist theatre, or which used to be replaced by two symmetrical staircases on the sides – as, for example, in the Kaunas Theatre (1892). The great staircase is not just a functional connection between different floors of the building – it is an important social space for the theatrical ritual. The environment formed by the stairs seems to emphasize those who climb them, drawing attention to them and allowing them to make visual contact with each other.

In the Michniewicz and Parczewski theatre, the great staircase is the only important element of the interior that does not obey the traditional harmony of symmetry. Although there are two symmetrical staircases in the corners of the building, contrary to what was usual, only one of them is open and developed – the left one. Its asymmetrical position has to do with Art Nouveau aesthetics, which broke the compulsory regularity, although the rest of the building’s structure is still traditionally symmetrical.

This change, together with the modest interior decoration and the solutions of the auditorium that did not live up to expectations, at that time were criticized in the press. In the architecture of the theatre, not so much attention was paid to the ritual, an important component of which was a sense of luxury. If in the 18th century theatres were still mostly installed in the manors of nobles – then later, after the democratization of theatres, the theater had a long-standing impression that they were entering a building close to the palace. The connecting space of the theatrical ritual – the lobby on the first and second floors and the staircase connecting them – decorated with rich terracotta red after reconstruction in 1926 to highlight the impression of luxury that may have lacked the original interior. Traces of polychrome can be seen in the exposures of the corridor walls – interior restoration projects were based on them.

The foyer is a room that originated from a small concert hall and became an integral part of the theatre in the 19th century. Unlike in later times, in the theatres of Historicism, the foyer was separated from the corridors and stairwells as a separate room, often not inferior in its splendour and luxury to the main room of the theatre – the auditorium.

In the Polish theatre, the foyer is a small, but probably the last legacy of the great tradition in the architecture of Lithuanian theatres. In later theatres, this room disappeared, merging into common corridor and stairwell spaces. The foyer of the Polish theatre is marked by the most ornate caisson ceilings in the theatre, formed by intersecting reinforced concrete beams and forming a geometric drawing typical of the late Art Nouveau, and two spacious semi-circular niches. The former image can be imagined by thinking of connecting two separate rooms on the first and second floors, into which the ceiling of the former foyer was divided during the reconstruction in the 1940s. Yes, on the one hand, the additional hall on the second floor, which was intended for rehearsals, was functionally used – after the relocation of the State Opera and Ballet Theater from Kaunas. On the other hand, the ornate space of a middle-class theatrical ritual was transformed into a utilitarian café room with a double lowered ceiling. Vilnius architects highlighted the height of the former foyer by forming openings in the upper part, which lead into the corridor of the second floor. Walking through it towards the upper balcony of the auditorium, both the space of the large foyer and the visitors of the theatre who came for a walk in it during the breaks were perfectly visible through the openings. The locations of the former openings are now marked by shallow niches.

The change in the balconies and lodges of the auditorium from the construction of the theatre to the Soviet period reflects well the social changes in society.

The architecture of the newly built Polish theatre has been sharply criticized, perhaps most of all for its inadequate auditorium space. The height of the hall was too high, the second-level balcony was too high and the reinforced concrete partitions were too high – for these reasons the visibility of the stage was very poor from some places, and due to the high partitions the male audience could not watch the women sitting on the orchestra seats. Shortly after the construction, the first reconstruction of the hall was started, during which the reinforced concrete partitions of the balconies were lowered by 40 centimetres.

Initially, the side parts of the first-level balcony were divided into lounges with low partitions – this was still a rudiment of the old class-divided society. Each lodge was accessed through a separate entrance (these entrances were later covered). The lodge is a cosy closed space that protects privacy and defines the social status of the spectator. Historically, private lodges occupied the entire perimeter of the balconies and only with the democratization process were they gradually replaced by open rows of chairs.

When the building was adapted for the Opera and Ballet Theatre in 1947, the balcony of the auditorium underwent the most changes. A characteristic mirror of Soviet society is the first-level balcony. During the reconstruction, 10 side lodges were removed and a new nomenclature lodge for high-ranking Communist Party members was designed in the central part of the former open balcony. Instead of a structure reminiscent of a class society, a structure reflecting a new hierarchical system has emerged.

As the necessity for technical equipment increased, the upper balcony amphitheatre was reduced during the reconstruction in 1975 (architect Nijolė Kazakevičiūtė). The top 5 rows were separated by a masonry partition and behind them, the necessary technical premises were installed, as well as a separate cabin for the sound operator at the back of the ground floor. Although the auditorium was heavily criticized for its poor visibility, its sound features remained unchanged – and to this day it is the theatre hall with the best acoustics in Vilnius.

The two most important rooms of the theatre – the auditorium and the stage – merge into one space, where the contact between the audience and the actors takes place. This place, which combines two different spaces – open, public and closed, intimate, mysterious – is marked by the proscenium arch. It sets boundaries to the stage action, separates and frames it like a picture. The image formed by this arch, like a film frame, is unique in every theatre. The original framing of the proscenium arch of the Polish theatre was in the shape of a regular square – with right angles and, like the railings of the balconies, decorated with an expressive strip. However, already during the reconstruction in 1925 (architect Julijusz Kłos) the proportion of the arch was changed: it was significantly lowered and widened, the decor was completely abandoned, and the former right corners were rounded. We see this modernized view of the proscenium arch today.

The stage was also reconstructed to improve visibility. Its floor level were lowered and the stage itself was brought closer to the spectators – a stage of a convex contour with a covered orchestral pit was formed. The entire floor of the stage was updated in accordance with the constructive – the wooden columns have been replaced with brick ones. The stage was once again reconstructed by adapting the building to an Opera and Ballet Theatre – the orchestra pit further expanded, significantly protruding into the auditorium space. The stage was reconstructed again in 1975 and 1983, adapting the building to the Academic and Youth Drama Theatres that operated briefly here. The space of the stage was adapted to the new needs: the curvature of the avant-scene was straightened again and the orchestra pit reduced, the current technical premises installed below the stage.

The current building of the Old Theatre of Vilnius, which housed at least 7 Vilnius theatres in different decades throughout the 20th century, despite its signs of Art Nouveau thinking in its architecture, is still a continuation of the historicist tradition. As in the old theatres of the 19th century, the technical part of this building is not very developed, especially compared to the theatres built later. However, it is much more developed compared to Kaunas Theatre – the Vilnius stage has small niches on the sides and a deep arrière-scene, as well as staff premises on both sides of the stage, to which two stairs lead. The largest room in the technical part of the building is a painting workshop. It was used to create, produce and paint large-scale hanging decorations, which formed the main part of the whole scenery. The Polish theatre painting workshop was located on the third floor above the arrière -scene, a wide opening connected it to the stage: the decorations could be sent down directly into the stage space through this opening. Specific lighting was also designed for the workshop room – three windows on the northern façade and a glazed roof strip. This provided the necessary natural indirect lighting. This bright room, like the windows in the arrière-scene, lit up the stage itself during daytime rehearsals.

However, when the building was adapted to the largest Lithuanian Opera and Ballet Theatre in the 1940s, these spaces were not enough. In 1950, a technical annex with a decoration warehouse and other premises was built on Mindaugo Street next to the theatre, and it was connected to the arrière-scene of the theatre by a curved gallery, which conveniently moved the decorations from the warehouse directly to the stage space. An auxiliary room has been installed in place of the former painting workshop, after covering the glass roof and building an opening connecting it to the stage – this currently is the Small Hall of the Old Theatre of Vilnius of Lithuania.

https://youtu.be/Tc7Wc8IQpYY

Alexandrowiczowa, Maria, Dzieje teatru wileńskiego, 1938, Wilno

Bohusz-Siestrzeńcewicz, Stanisław, Wilno i estetyka, 1916, Wilno

J. Sz., Reduta w Wilnie, 1925

Alexandrowiczowa, Maria, Dzieje teatru wileńskiego, 1938, Wilno

Bohusz-Siestrzeńcewicz, Stanisław, Wilno i estetyka, 1916, Wilno

J. Sz., Reduta w Wilnie, 1925

Korwin-Milewski, Hipolit, Pohuliankos teatro gimimas, Krantai, 2013, Nr. 3

Lietuvos architektūros istorija, t. 3, Nuo XIX a. II-ojo dešimtmečio iki 1918 m., red. A. Jankevičienė et al., Vilnius, 2000.

Lukšionytė-Tolvaišienė, Nijolė, Vaclovo Michnevičiaus kūriniai Vilniuje, Kultūros paminklai, 2001, Nr. 8

Nowy teatr wileński, Tygodnik illustrowany, 1913, Nr. 44

Tidworth, Simon, Theatres. And Architectural & Cultural History, New York, Washington, London, 1973.

Lietuvos Mokslų Aakademijos Vrublevskių Bibilioteka, Rankraščių Skyrius, F229-1791, F229-1797, F229-635

LVIA, 1135 fondas, 12 apyrašas, 66 byla. Vilniaus universiteto profesoriaus architekto Juliaus Kloso asmeninio archyvo dokumentai, susiję su „Redutos“ teatro 1925 m. perstatymu: planai, brėžiniai, susirašinėjimas, sąmatos, skaičiavimai, laikraščių iškarpos ir kt.

LVIA, 1135 fondas, 12 apyrašas, 636 byla. Vilniaus universiteto profesoriaus architekto Juliaus Kloso asmeninio archyvo Didžiojo teatro Pohuliankoje perstatymo darbų dienoraštis.

Vilniaus regiono Valstybės Archyvas (VRVA), 1036 fondas, 11 apyrašas, 1 byla. Rusų dramos teatras Vilniaus mieste. 1946 m.

VRVA, 1036 fondas, 11 apyrašas, 14 byla. Rusų dramos teatras Vilniaus mieste. Priestatas. 1950 m.