address

A. Vienuolio g. 1

number of theatre staff

630

auditoriums

2

theatre building opened

1974

texts

Kostas Biliūnas, Artūras Savko

Initially in post-revolutionary Russia and later in the Soviet Union, opera was regarded as an art that belongs to bourgeois society. It certainly was, encompassing not only the repertoire of the imperialist 19th century, but also the very ritual of going to the theatre, in which, as in probably no other type of entertainment, elitism and the pursuit of luxury are so clearly revealed. All this could not match the Soviet concept of „art belongs to the masses”. Just that there was one problem: opera was extremely popular. Given the great demand of the population, it was necessary to integrate this historical genre into the cultural field of the Soviet Union, and for long quite some time composers searched for a musical language of Soviet opera.

Since 1940, in Soviet Lithuania, the search for a place and architectural expression for the opera house had also begun – it would replace the theatre in Pohulianka, built for money donated by the middle class. The building was to become part of the structural transformation of the new Vilnius. A representative place for the theatre was looked for in Naujamiestis – construction on Pamėnkalnis hill was considered, yet later a project was prepared in Mindaugas str. (approximately on the site of the current “Maxima” supermarket). It was also thought of a land lot near the Neris river, where a wood-gas factory had been operating since the 1860s, supplying gas to the city’s lighting. The factory operated until World War II, at the end of which it was blown up and no longer rebuilt. In 1945, the territory of the former factory was fixed up and a small square was settled there.

In the 1950s, proposals for a new Opera and Ballet Theatre building on the site of the Neris river were submitted by Moscow architects, and by the end of the decade, two variants with proposals from Vilnius and Kaunas architects. The final competition took place in 1960, and was won by Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė with a brave project of modernist architecture that had just returned to the field of actuality. It was later retouched, refined, some parts transformed, but the essential architectural expression remained the same until 1968, when construction began. Through then, the theatre project gradually changed to refine the interior solutions and details, and in 1974 it took on its current form.

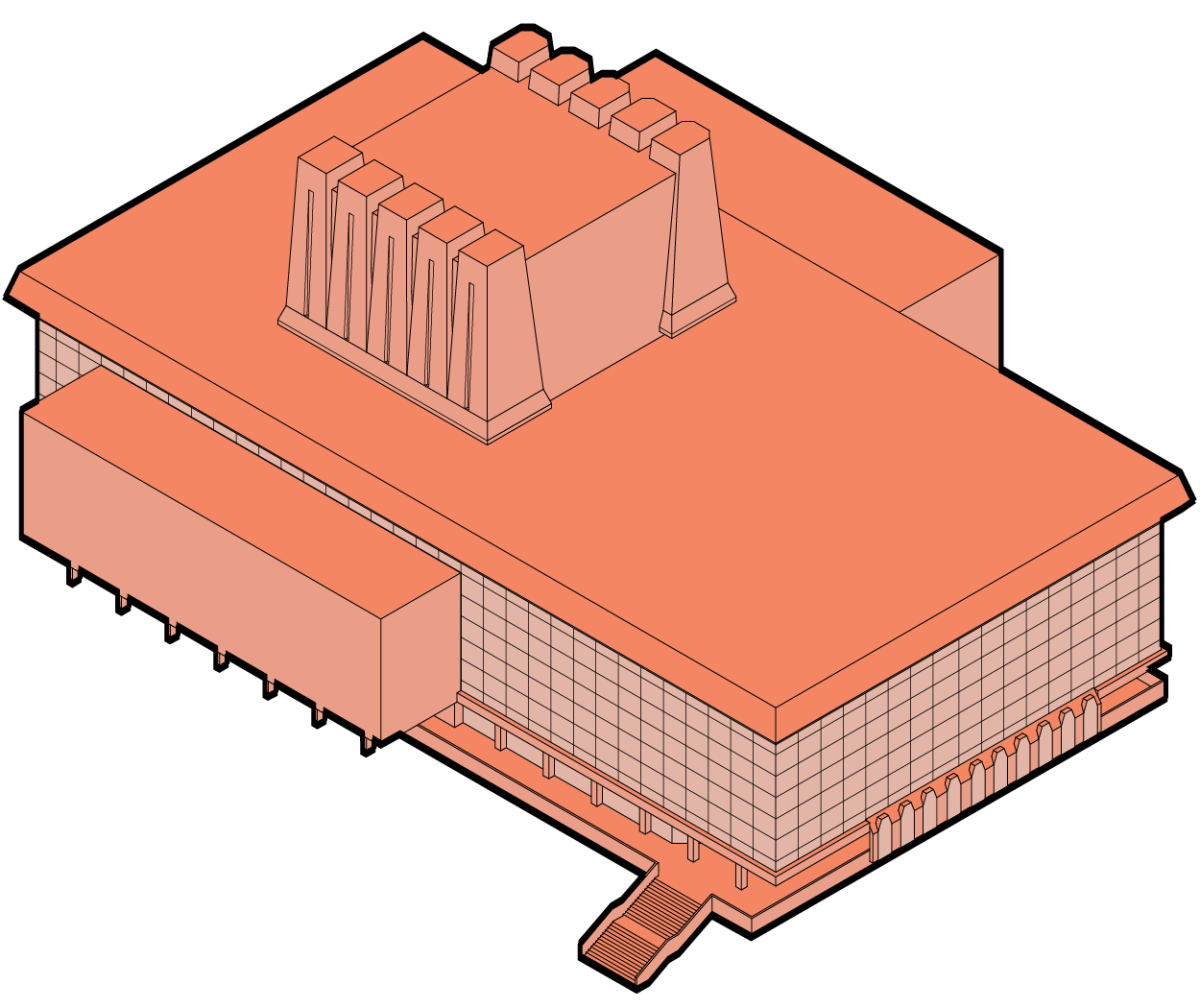

The current image of the Opera and Ballet Theater was never conceived and implemented as a single architectural work. In fact, the project underwent transformations and changes that took place ever since its construction began. It could be said that the original project of the early 1960s is reflected in the structure, volumes and composition of the building. However, the materials, textures, fine-grained interior and exterior decoration as well as the sculptural design elements are the result of a completely different, further and distinctive, personal contribution from the creators of the building. The concept of the Opera and Ballet Palace was never homogeneous. It still shows traces of both refined, functional, clear post-war modernism and unpredictable, dynamic, complex late modernism. If the former in a simplified manner could be associated with the word ‘lightness’, the latter would be more appropriate for the antonym ‘heaviness’. Two almost radically different concepts, the approaches of two periods of modernism – the lightness of volumetric plasticity and the sculptural heaviness of forms – are housed in one exclusive theatre building in the history of Lithuanian architecture.

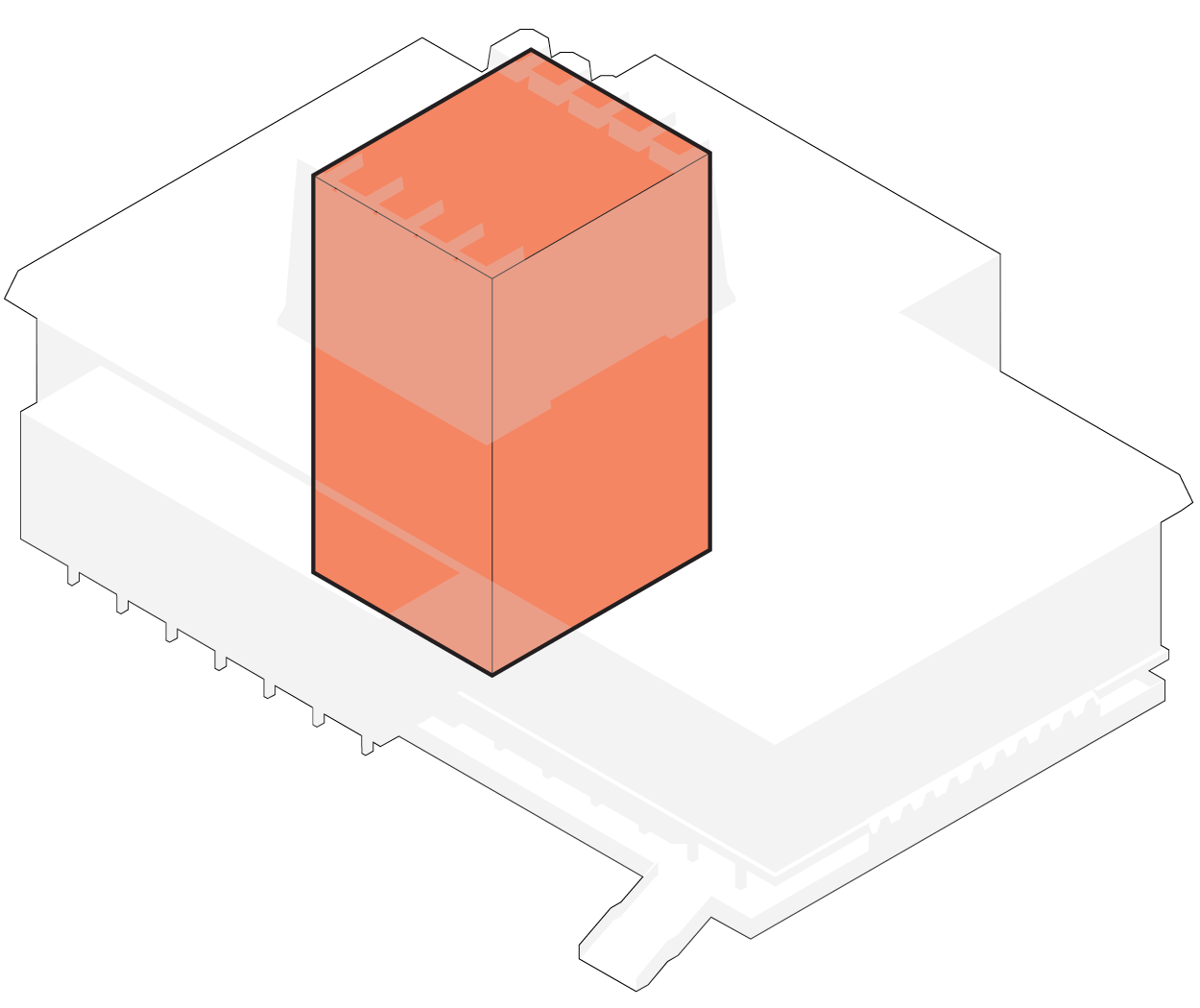

The essence of the composition of the Opera and Ballet Palace is a classic solution in modern architecture – a rectangular parallelepiped volume suspended athwart a descending slope. It is this, not smooth, but gently descending relief of the plot, that allows the building to be in constant contact with the environment, as if never at rest. The representative symmetry characteristic of previous projects of socialist realism has been abandoned – the theatre building is best viewed from the side, which opens onto a wide public space. An undeveloped area is necessary to be able to contemplate and understand a huge building. The public space is like a modern interpretation of real nature, where on the descending slope the steps of the stairs intertwine with the cascades of water falling from the fountain. The authors of the wide square are architects Algis Knyva and Aleksandras Lukšas. In the modernized landscape, which provides the space needed for a large theatre, the most important natural feature of this place is the slope.

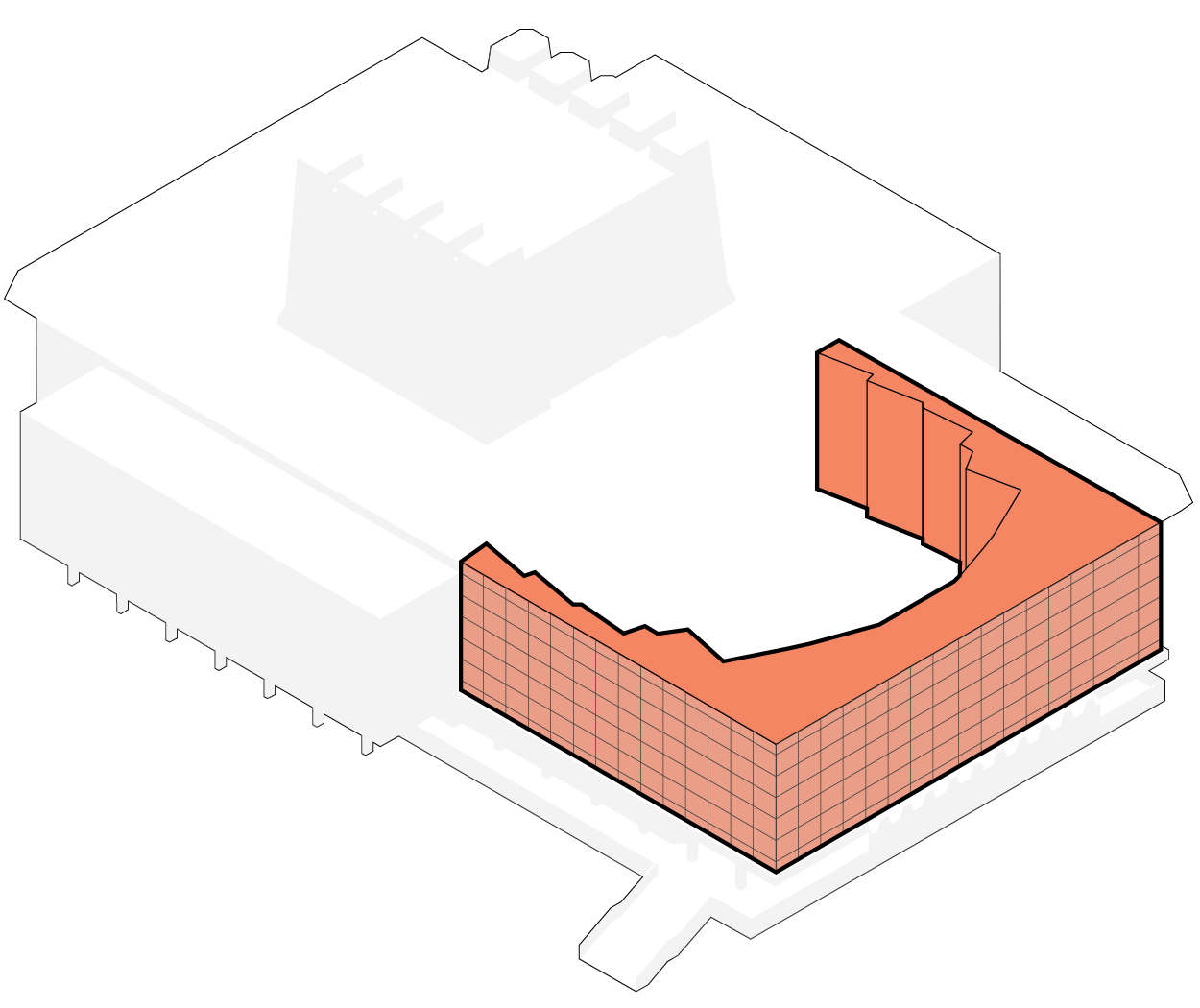

When designing the theatre building, the environment around it was imagined a little differently from what it looks today. The main transparent facade overlooks the Neris Valley and St. Raphael Church, but the connection with the river today is blocked by a traffic ring, trees and the building of the former Museum of the Revolution (now the Vytautas Kasiulis Museum of Art), which was then planned to be demolished. The theatre’s connection to the river and its other banks is still there, though not as direct. Simplifying the entire volume of the theatre, we could see a building made up of two equal parts: a stable, closed part of the stage and a hanging, transparent part of the auditorium. If the first rests firmly on the horizontal surface of the earth, then the second – such was the architect’s original vision – is not only transparent, covered with hanging, meaning an unsupported by columns roof, but still rising above the descending slope. The simple and accurate sense of space still makes an impression in the face of the glass part of the theatre. However, this impression diminished with the closure of the pedestrian passage under the building. It used to be a free passage on the ground floor around the lobby on all sides, which highlighted the lightness of the glass rectangle hanging over the river valley.

The arcade, like the whole „light” side of the theatre, was intended for theatre-goers and all the citizens. There used to be press and flower kiosks, posters, and the entrances to the box-office lobby on the side of the arcade. After the reconstruction in 1997, the open space accessible to all became the theatres’ offices and the chamber function hall. With the doubling of the number of employees since the construction of the theatre, the need for new premises became inevitable, and the theatre is constantly updated with new development projects.

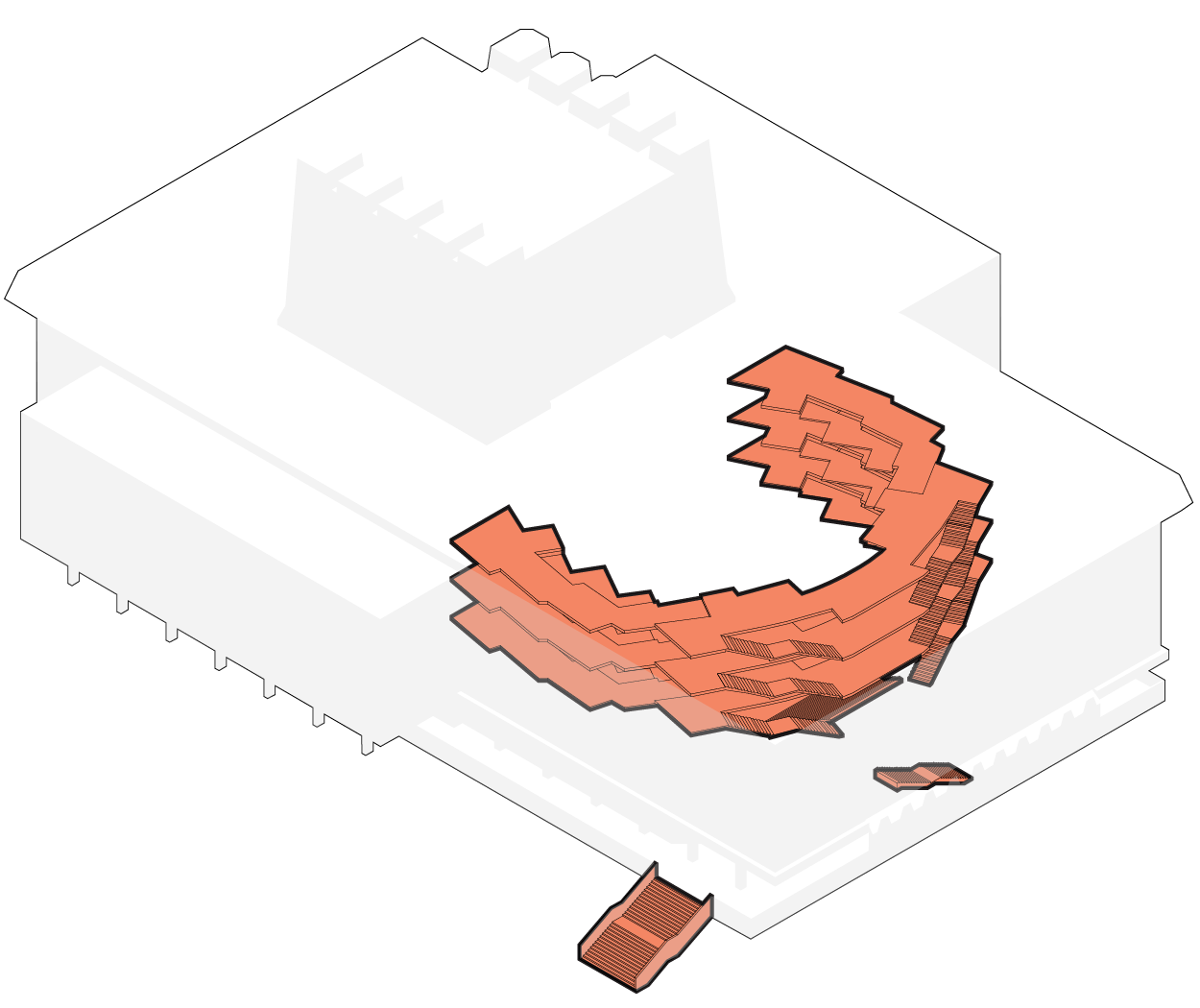

Even after undergoing cardinal modernist transformations, the architecture of the theatre nevertheless retained certain elements of the traditional theatrical ritual that was formed in the epochs of Neoclassicism and Historicism. The most striking element of this already forgotten and broken tradition in Bučiūtė’s architecture is the element of the staircase. This luxurious, symmetrical staircase is not only taken from the old theatre architecture, but it is also the most developed in this building. The stairs are probably the most important factor in creating a „theatrical” atmosphere at the Opera and Ballet Theatre.

The motif of the ascent up the stairs begins before entering the building, just looking at it from a distance – from the fountain decorated with large steps and together with the relief, the outdoor stairs rising from the river side. The first front stairs meet us outside – being something more external than part of the building, they connect the lower and upper passages. The intricate system of open spaces envelops the transparent side of the theatre. The stairs, together with the open galleries and the arcade space emphasize the lightness of the glass volume that hangs above them. The other staircase leading to the building leads from the box-office lobby, a more intimate alternative to the traditional ceremonial staircase on the outside. In total, the main entrance to the theatre can be reached in three different ways, thus reducing the importance of the main stairs and highlighting the democratic nature of the architecture.

While the outdoor staircase offers a variety of alternatives, the main staircase inside the theatre – the great staircase – is the element that contains the highest concentration of a traditional theatrical ritual. Visitors who enter through one side of the building from a dispersed exterior are oriented towards harmonious symmetry. The stairs from the horizontal dimmed marble foyer effectively lead to a vertical, open and bright red lobby. Almost a baroque spatial drama is concentrated in this place of the building: every time one climbs the stairs from everyday life to a celebration. This transformation, this strong dramaturgy is shaped by the language of modern architecture.

The motif of the ascent does not stop on the grand staircase, the symmetry it introduces unfolds in two blocks of stairs that connect three more floors of balconies and boxes, creating the impression of a never-ending ascent.

The most famous room of the Opera and Ballet Theatre – the red lobby, which belongs not only to the theatre building, but to the whole city, was an integral part of the original project of the 1960s. Such a modern interpretation of a traditional theatre building with curtain walls opening the large lobby to the city was created by a team of German architects led by Werner Ruhnau. Built in 1959 in Gelsenkirchen, West Germany, the theatre designed by these architects became a source of inspiration for the modern Vilnius theatre project.

The original version proposed was indeed close to the German prototype, with a glass curtain wall enclosing the auditorium on three sides and the geometry of the staircases displayed behind it. However, the 14-year-old project has become more distinctive and original. If the interior of the main lobby of the Ruhnau Theater is extremely modern, and its only accent are the industrial style reinforced concrete columns, then the impression of the Bučiūtė Theatre is radically different. In a successful collaboration with Russian designer Yuri Markeev, the spacious interior of the main lobby (like the spaces of other rooms) was enriched with shapes, colours and textures. Ascetic post-war modernism is often accused of uncosy, cold, non-human-scale spaces – the tandem of Bučiūtė and Markeev evades this. The sterile glass box in the red lobby is filled with interior elements as much as possible, with 72 brass and yellow glass chandeliers made by the East German company “Heimel Elektrik” – the culmination of this architectural dramaturgy.

In a traditional 19th-century theatre, the interior of the main lobby, a room similar to a palace hall, reflects the luxurious entertainment of middle-class theatre-goers – something we might call elitism. Built during the Soviet era, the Opera and Ballet Theater in Vilnius is not for bourgeois entertainment (it even sounds like an anachronism), it is for the entire population, it is democratically open to the city, allowing it to pass through and inviting to enter by several different roads. Inside, surrounded by yellowish lights and luxurious materials, an ordinary citizen of the Soviet republic is given the opportunity to feel in a different reality of a theatre. This building ignites the hope of an escape from grey everyday life for every visitor.

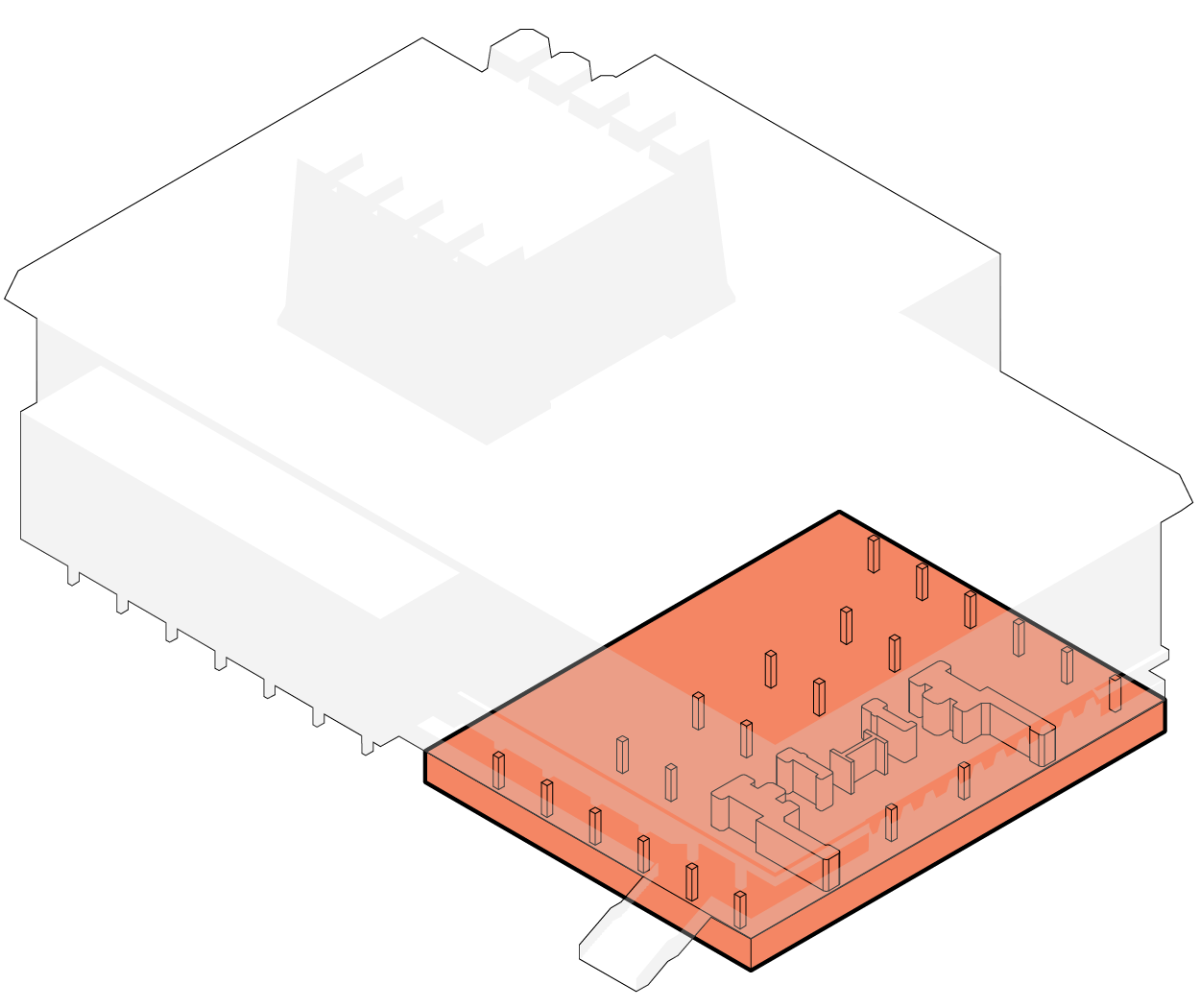

Eight doors lead to the ground floor of the auditorium of the largest theatre in Lithuania. Initially, there were 1,150 seats here. After the renovation in 2005, the number of seats was reduced to 984 by replacing the chairs. The moss-coloured tapestry chairs were replaced by wooden ones with red tapestries, and the carpet was replaced with a hard floor covering with better acoustic properties. The rest remained unchanged.

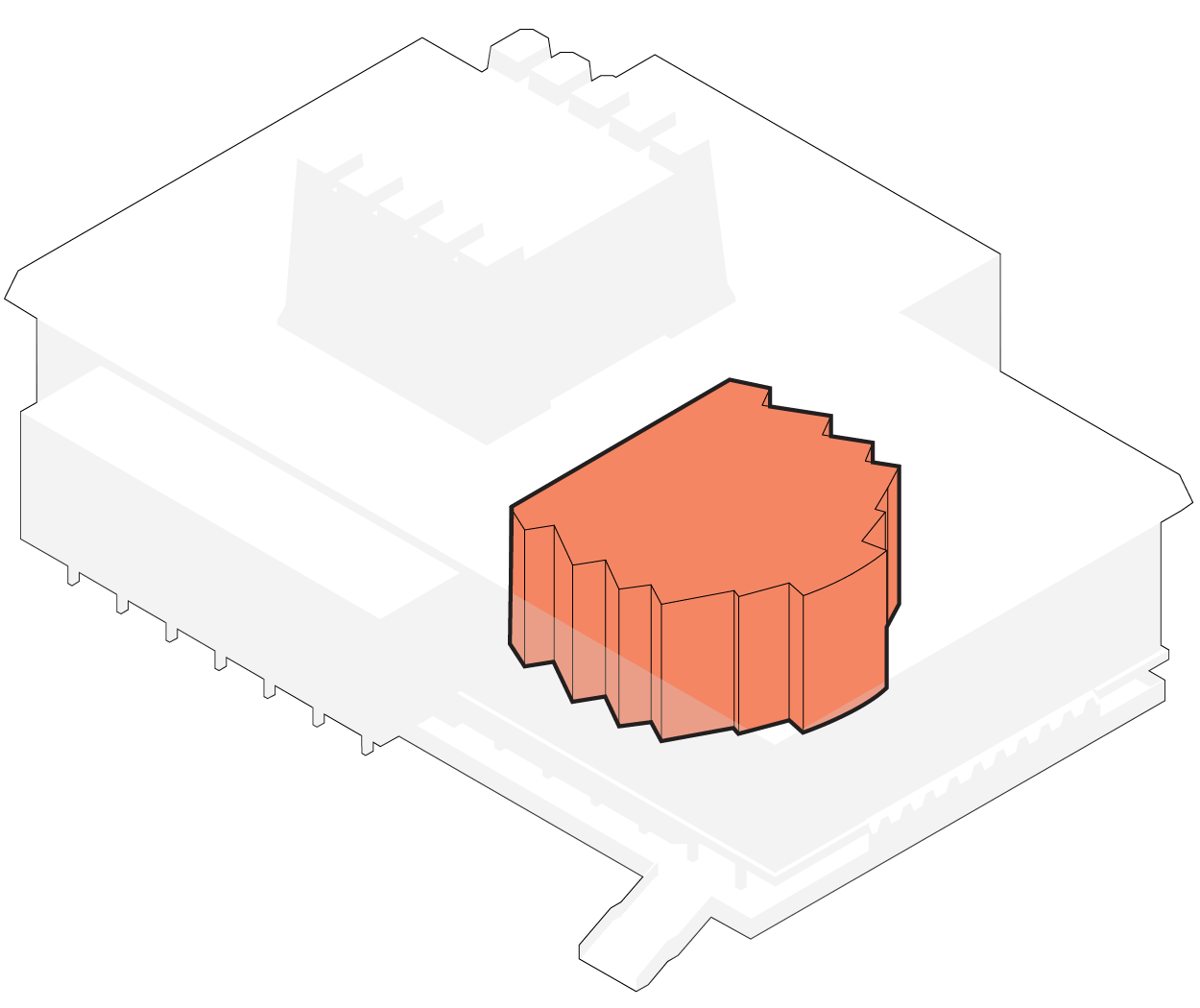

The auditorium of the Opera and Ballet Theatre is a unique interpretation of the so-called horseshoe-shaped hall, which was formed in the Baroque era. The architecture of the building, from the modern and freely treated connection with the surrounding environment, gradually brings the theatre visitor to the hall with an almost traditional structure. Such a change is not accidental, but is specially planned to gradually prepare the viewer for the awaiting theatrical event, focusing on the oldest and most traditional genre of music – opera. Although the structure of the auditorium is inherited from the tradition of old theatres, the interior as a whole is probably the richest example of late modernism in Lithuania, dominated by red ceramic tile walls, dark African teak veneer logs and similar to these, extending their sculptural forms – an acoustic ceiling.

As in other rooms, 5 types of finishing tiles created especially for this theatre by Markeev and made of Latvian clay in the Jašiūnai experimental factory are used to decorate the walls here, which blend into the whole combination of warm shades in different proportions throughout the theatre interior: clay, wood and brass. Until 2005, this combination was easily cooled by the greenish-mossy tapestry colour of the chairs, giving refreshment to the rich brown tones. The interpretation of traditional theatre culminates where the audience meets the stage – the proscenium arch. Its framing, reminiscent of a cinema screen, is contoured by a luxurious profiled frame – as is usual for an opera house, with gently sloping arch corners.

The biggest theatre stage in Lithuania was a stark contrast to the ensemble that moved from Pohulanka Theater in 1974. If the old theatre, the stage of which was reconstructed by Julijusz Kłos in 1926, needed 15 workers to serve the stage, the new theatre needed 60 of them. A comparison with the old Pohulanka building, where the Opera and Ballet Theater operated from 1948 to 1974, can best reveal the possibilities offered by the new theatre and explain the confusion of the theatre staff when starting to work with the new systems.

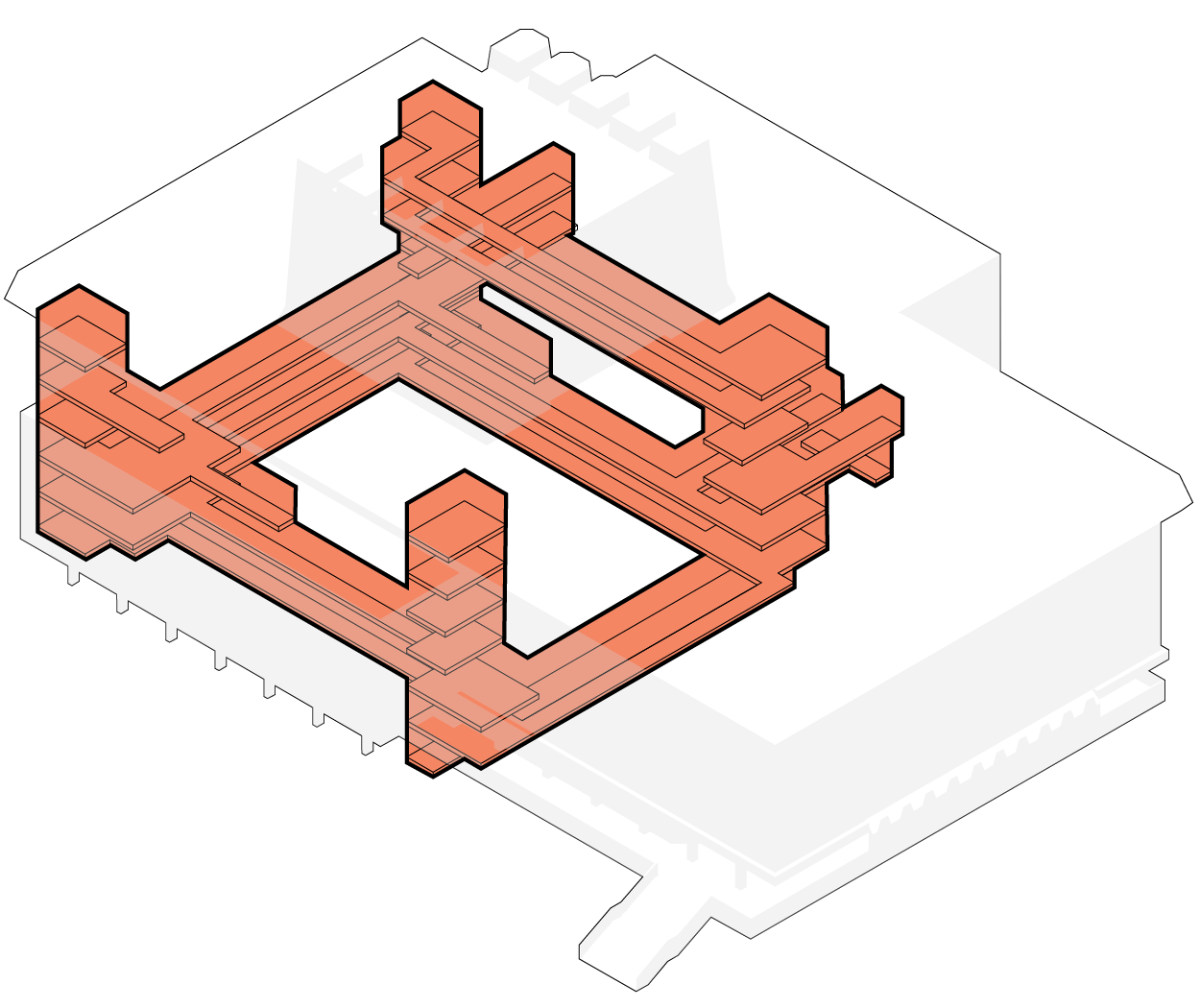

The stage is about 5 times larger than the old theatre on Basanavičiaus Street, and the complementing spaces are 7 times larger. The theatre scene has not only an arrière-scene, but two deep (scene-wide) wings. If traditionally the largest service space was at the top of the stage, here these spaces expand in all other directions as well. The hold under the stage floor is the most technically complex space, housing all the equipment that transforms the stage floor. During the 2006-2009 renovation, the worn-out equipment, which was brought from Dresden in East Germany during the construction of the theatre, was replaced enabling the formation of two main variants of the stage floor. In the first case, the floor of the stage consisted of a platform with a rotating ring of 17 m in diameter with a smaller rotating circle in the middle. In the second case, this platform could be pushed deep into the cassette behind the arrière-scene, and the floor of the stage was formed from the rectangular pitches rising from below, as if piano keys that raised and lowered, creating the floor relief needed for the scene. The orchestra’s pit was also transformed – it’s bottom can been raised if necessary.

In addition to the exceptionally spacious wings, the largest stage in Lithuania is also characterized by the highest height among the rooms – it consists of a stage box rising quite some more above the building itself. Such a massive dome-like superstructure, like a building on a building, is often sought to be hidden in theatre architecture, since it’s an inorganic but necessary technical object. Bučiūtė’s theatre did not follow this path, on the contrary – the stage box is dominant here, reminiscent of a huge sculpture of blackened copper. It reminds a heavy stone holding the whole technical part of the theatre.

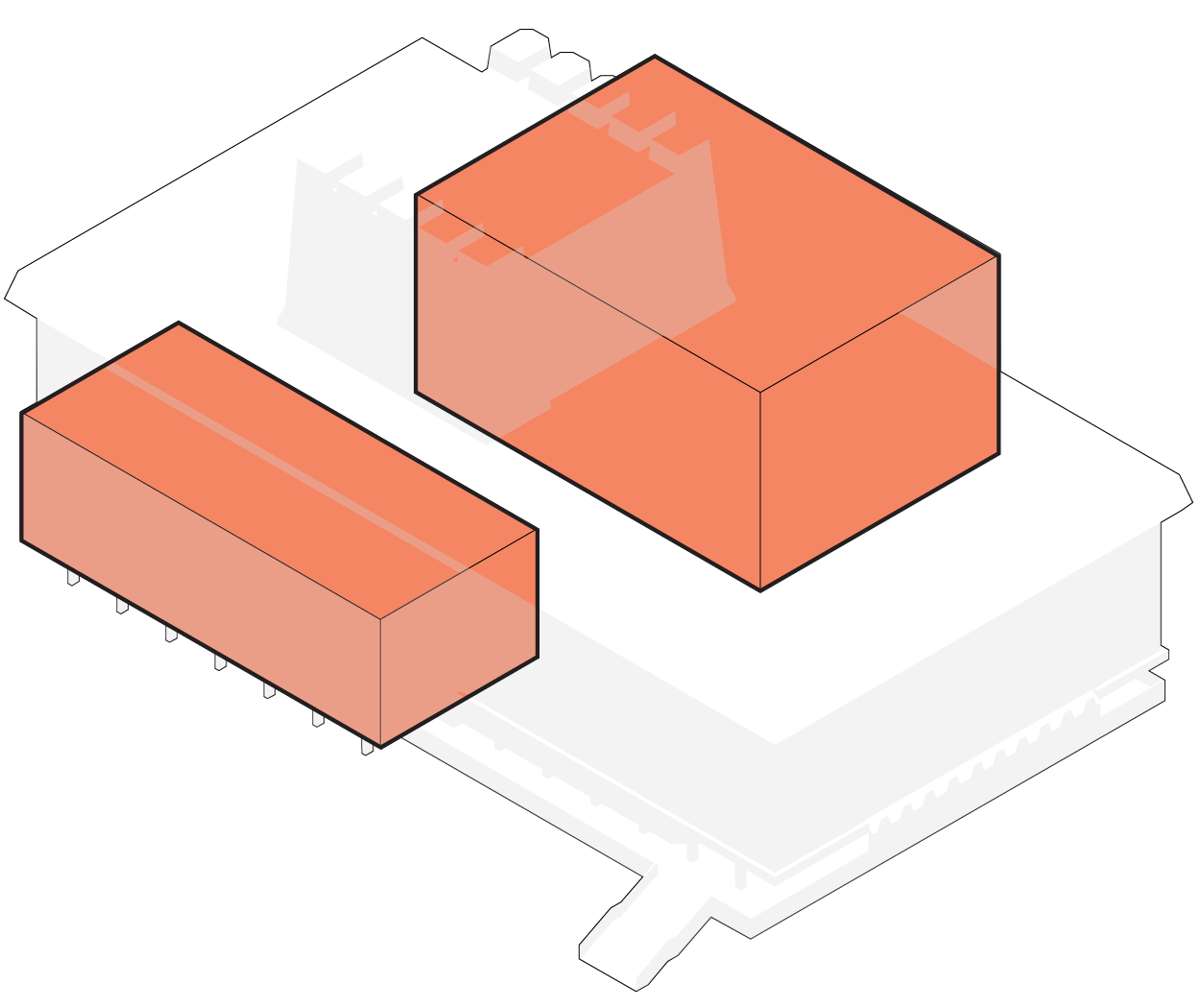

As a counterweight to the transparent part of the theatre that hangs over the Neris Valley, the part of the building serving the stage is much more enclosed, stably resting on the ground and covered with a 16 m high stage box covered with copper plates. The administrative premises are concentrated on the facade overlooking Lelevelio Street, and the functional premises are rationally divided into two groups. The technical decoration zone is located at Vienuolio street and the ballet and choir artists’ rooms to the opposite, on the side of the square. Passing through the theatre building, a well-visible white vertically striped façade shields the main rehearsal spaces. The former joint opera and ballet rehearsal hall is now used for ballet rehearsals. Its area is slightly smaller than the one of the great stage. Simulating the theatre scene, the hall is decorated with dark wood and illuminated only through skylights. The small balcony above has access to the former office of the theatre manager.

In the other corner of the white volume visible from the side of the square, there is a small rehearsal room for the choir, and it is also lit only through the skylights – meant to help the artists concentrate in their work, not get distracted. Since the theatre was built, the number of employees at the Opera and Ballet Theatre has doubled and now stands at 600 – the need for new spaces is big. There is a lack of a spacious rehearsal room, administrative premises. Currently, the construction of a technical annex is planned on the adjacent plot, on the site of the parking lot.

The technical premises protrude asymmetrically towards Vienuolio Street – are mainly used for the production of decorations and logistics. An analogous blind façade here hides a spacious interior atrium illuminated through skylights. Decorations are brought in and out through the gate leading to it. The scenery is raised to the stage level by a 20 m long ramp and can directly reach the stage space. A wood and metal workshop is located next to the technical atrium. The traditional room of the theatre structure, inseparable from the production of decorations, the so-called painting hall, as usual, is located on one of the upper floors.

The theatre building is made up of two contrasting parts – a „light” one for the audience and a „heavy” one for the theatre staff. While the architectural character of the light part is best revealed in the spacious red lobby with giant windows and chandeliers, the spirit of the enclosed, stage-serving part of the building does its’ best in the long and expressive corridor spaces. They are an essential element for the whole stage: darkened, illuminated only by the glazed staircases in the corners. Here there is a constant movement of staff, various sounds and smells spreading and mix together, and the opening doors reveal the ever-changing components of a musical theatre that encompasses all the arts. The four corridors connecting the lower floors of the building cover a variety of premises, connecting them into a cohesive, closed world of theatre.

In the technical part of the building, the same combination of warm tones is repeated only in a slightly more modest manner: clay, wood and brass. The warm dark colour dominates, supported by artificial light emanating from the yellow glass chandeliers. Plates decorating brass columns, made in Trakai district, replicate the decoration of columns outdoors. Corridors in different floors do not repeat, they are either narrow or wide. Plaster, wood and textiles are used for wall decoration, metal is used for the columns. Functional furniture designed by Eugenijus Gūzas. The small theatre staff canteen is accentuated by the bright metal composition of Algimantas Mizgiris. This work seems to concentrate the whole expression of the architecture and design of the theatre.

The structure of the Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre is a complex autonomous organism. Each part of this building and group of premises are an original architectural element. This is characterized not only by the public spaces, but also by the ones intended for theatre staff – after all, they are the ones who spend the most time in the building. This is a distinctive feature of this theatre, which is characterized by only a few buildings even among exceptional architecture – continuous architecture from the outside to the inside encompassing urbanism, volume plasticity, function, the interior and its smallest details. Due to these features, it is an exemplary piece of architecture.

Abbate, Carolyn, Parker, Roger. A History Of Opera. The Last 400 Years. Penguin Books, 2015.

Ave, opera, Kultūros barai, 1974, Nr. 10

Baginskienė, Danutė , Architektė Nijolė Bučiūtė, Statyba ir architektūra, 1976, Nr. 1

Būsimasis Vilniaus operos ir baleto teatras, Statyba ir architektūra, 1963, Nr. 1

Kobzakowski, Jerzy, Projekt regulacji częsci wybrzeza i srodmiescia między ulicami Wilenską, Jakoba i placem Lukiskim, Prawda Wilenska, 1940 IX 22

Lapinskas, Anatolijus, Kaip buvo statomas teatras. Iš buvusio teatro direktoriaus Vytauto Laurušo prisiminimų. Bravissimo, 2014, 3, 81-83.

Markejevaitė, Lada, Žvilgsnis į LNOBT architektūrą. Rūmų kūrimo istorija (1960–1974). Bravissimo, 2014, 3, 81-83.

Mickus, Petras, Gausėja keraminių gaminių pastatų apdailai, Statyba ir architektūra, 1976, Nr. 5

Ruseckaitė, Indrė, Markejevaitė, Lada, Asmeninis Elenos Nijolės Bučiūtės modernizmas [interaktyvus] https://leidiniu.archfondas.lt/alf-02/indre-ruseckaite-lada-markejevaite-asmeninis-elenos-nijoles-buciutes-modernizmas

Tidworth, Simon, Theatres. And Architectural & Cultural History, New York, Washington, Lon